It’s been used since the Roman times, but concrete has never been more popular than today, with China using more of the stuff in the last three years than the United States in the last century. Concrete is one of the most widely used materials in the world, but at some point, no matter how it is mixed, it will crack and deteriorate.

It was to this problem that microbiologist Hendrik Jonker set his mind. Whilst thinking about how the body can heal bone through mineralization, he looked into whether a similar method could be used with concrete. By mixing it with limestone-producing bacteria, he found that any cracks that formed in the concrete were patched over. For this invention, Jonker is now a finalist for the European Inventor Award 2015.

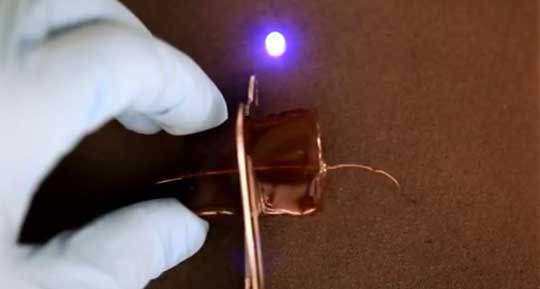

The bacteria, either Bacillus pseudofirmus or Sporosarcina pasteurii, are found naturally in highly alkaline lakes near volcanoes, and are able to survive for up to a staggering 200 years without oxygen or food. They are activated when they come into contact with water and then use the calcium lactate as a food source, producing limestone that, as a result, closes up the cracks.

He calls the material “bioconcrete” that can “self-heal.” In order to keep the bacteria dormant until it is needed, it is placed in small, biodegradable capsules containing the nutrient. When the concrete cracks, and water enters the gaps, it comes into contact with the bacteria and the food source, setting the healing process off. The bacteria then feed on the calcium lactate, joining the calcium with carbonate to form limestone, fixing the crack.

The process has been proven to work effectively, and can even be added to a liquid that could then be sprayed onto existing buildings. The problem, however, as always is the price. It is currently twice the cost of traditional concrete, but Jonker says that this is mainly due to the price of the calcium lactate, and if they can get the bacteria to use a sugar-based nutrient instead, the price would be dramatically reduced.

If they can sort out the pricing, then little would stop the incredible self-healing material from being used in bridges, tunnels, roads and other buildings, with the bacteria laying dormant for centuries and only ‘coming to life’ when needed.